Xenotransplantation of animal cells, tissues or organs into human beings is in the media spotlight after two recent surgical breakthroughs in the United States. In October 2021, a kidney grown in a genetically altered pig was successfully attached for close to three days to a brain-dead patient at the NYU Langone Transplant Institute in New York City, demonstrating the feasibility of using a new source of animal organs for xenotransplantation. In January 2022, surgeons at the University of Maryland Medical Center successfully transplanted a genetically modified pig heart into an adult human with terminal heart disease for the first time, with the patient surviving for two months.

Amid these notable clinical advances, a more favorable global regulatory landscape for xenotransplantation is likely to emerge over the next years, as PLS companies and investors press for more clarity on legal and ethical issues. Currently the US – the world leader in xenotransplantation surgery and R&Di – has specific domestic regulations concerning xenogeneic and cell-based products,ii as do Japan and the UK. China has yet to develop its own regulations, although the country’s scientists have made significant progress in recent years in developing genetically-modified pigs for transplant surgery. Regionally, the EU has its own set of xenotransplantation regulations while globally, the WHO recommends that member states should have effective national regulations before allowing animal-to-human transplants.

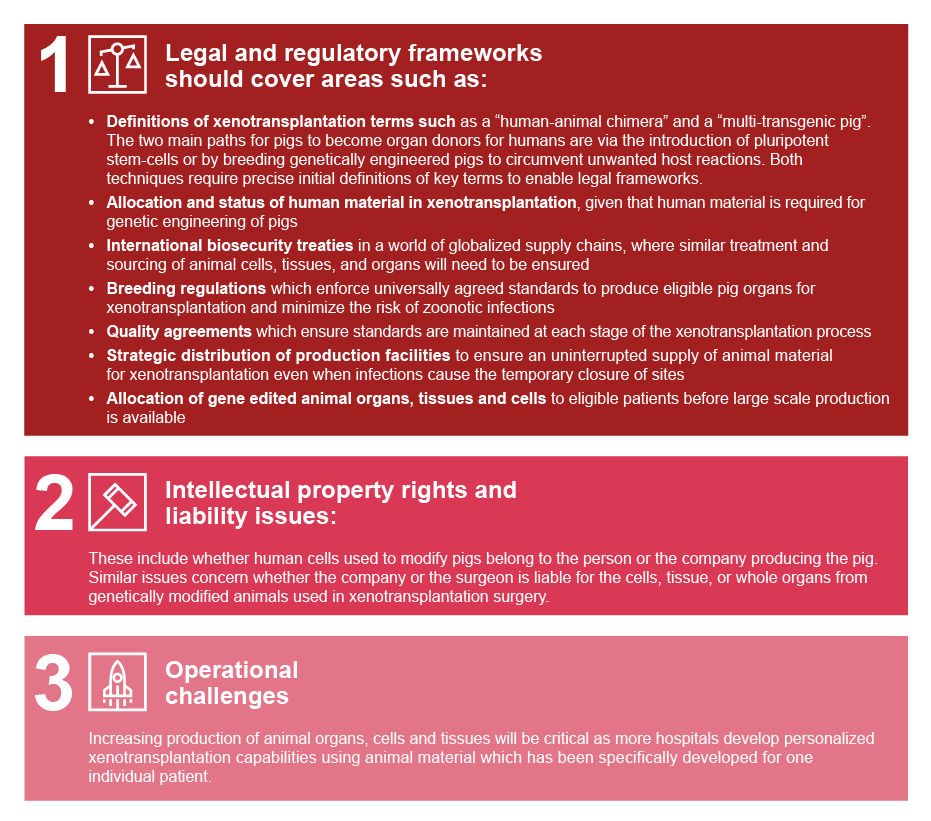

However, governments and regulators in these markets are struggling to keep pace with the sheer speed at which the science and practice of xenotransplantation is accelerating. Headline-making events such as the two US operations, and an increasing stream of groundbreaking research on the subject,iii,iv are generating debate about regulatory and intellectual property (IP) conundrums ranging from animal breeding rules to the allocation of gene-edited organs to patients before large-scale production exists.

i https://www.economist.com/science-and-technology/2021/10/20/a-pig-kidney-has-been-successfully-transplanted-into-a-human-for-the-first-time

ii Kwisda K, Cantz T, Hoppe N. Regulatory and intellectual property conundrums surrounding xenotransplantation. Nature Biotechnology | VOL 39 | July 2021 | 796–798 | www.nature.com/naturebiotechnology

iii Kwisda K, Cantz T, Hoppe N. Regulatory and intellectual property conundrums surrounding xenotransplantation. Nature Biotechnology | VOL 39 | July 2021 | 796–798 | www.nature.com/naturebiotechnology

iv https://www.economist.com/science-and-technology/2021/10/20/a-pig-kidney-has-been-successfully-transplanted-into-a-human-for-the-first-time

1. The potential market opportunity for xenotransplantation

Across healthcare, organ transplantation is widely established as a life-saving treatment for patients with end-stage organ failure.v However, worldwide demand for human organs largely outweighs supply, despite restricted organ eligibility criteria and broad donor eligibility.

In the US alone, the Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA) reports that there are more than 100,000 men, women, and children on the national transplant waiting list. Yet in 2022, there were only 14,905 deceased donors in the US and 6,466 living donors. At present, the US waiting list for kidney transplants is increasing by around 14,000 patients per year, while there are around 750.000 patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD).vi

Dialysis remains the sole treatment option for patients waiting for donors, but they only have a 40 to 50 percent chance of surviving for five years, compared with more than 80 percent for patients who receive a kidney transplant. Furthermore, the cost of dialysis treatment for five years is approximately 10 times greater than transplantation.vii More than 2 million patients worldwide who suffer from clinically diagnosed ESRD confront the same shortage of donor kidneys, with the number of undiagnosed cases almost certainly far higher.

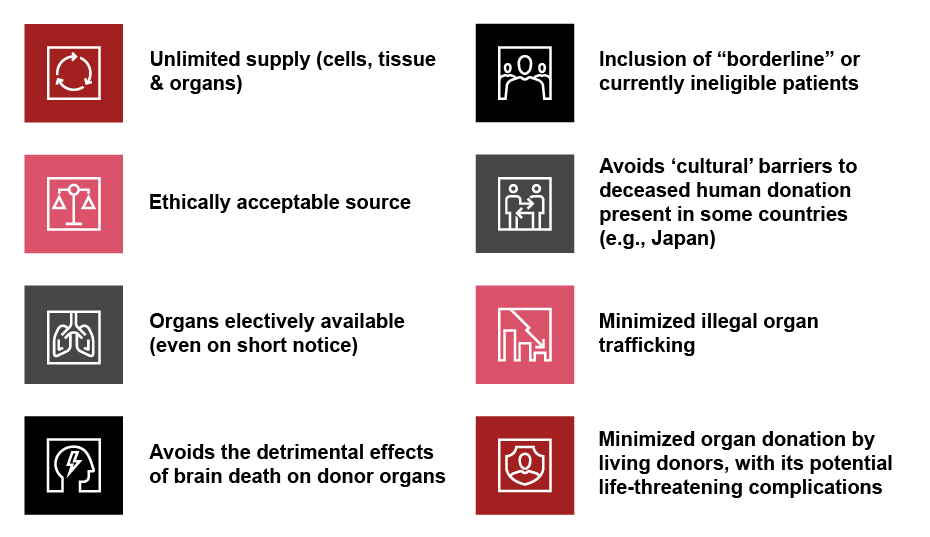

Kidney transplants are just one high-profile area where xenotransplantation has the potential to be used with various advantages for a wide range of disorders, provided the market and clinical practice are strictly regulatedviii,ix,x (see Exhibit 1). These include a supply of animal cells, tissue, and organs that can outpace demand for their human equivalent from ethical proven sources where the decision to donate was voluntary and based on informed choice. So far, only pigs have been bred for xenotransplantation research and surgery because they mature rapidly, typically have large litters, and have organs that are similar in size and function to human organs.

In the foreseeable future, as advances in xenotransplantation continue, animal organs could be electively available, even on short notice. “Borderline” or currently ineligible patients could be included, while avoiding cultural barriers to organ donation from deceased people in countries such as Japan. Increased xenotransplantation would also help reduce illegal human organ trafficking and the incidence of potentially life-threatening complications from living human donation.

Exhibit 1: Advantages of xenotransplantation

All these factors explain why market projections for xenotransplantation are rapidly rising. In 2020, for example, Orian Research, an industry research group based in India, forecast that the global xenotransplantation market would be worth $16bn by 2025 and $26bn by 2032, with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 7.13 percent between 2026 and 2032.xi

Such estimates need to be treated with caution, given that healthcare professionals, PLS companies and regulators are still respectively in the early stages of defining the market in clinical, business, and legal terms. Nonetheless, Strategy& believes there is already enough evidence for PLS investors to regard xenotransplantation as a major market opportunity.

One example among a growing number where the availability of solid animal organs could significantly increase the market’s size is for tumor patients without metastases. Another promising area is technological advances in pig tissue transplantation, which could enable diabetic patients to receive new pancreatic islet cells. Similarly, pig corneas could be used in eye operations or neuronal cells from pigs to treat Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease.

Exhibit 2: Disorders for which xenotransplantation is a potential therapy

Source: Based on Ekser B, et al. The Lancet (2012)xii

v Axelrod DA, Schnitzler MA, Xiao H, et al. An economic assessment of contemporary kidney transplant practice. Am J Transplant. 2018;18(5):1168-1176. doi:10.1111/ajt.14702

vi Hart A, Smith JM, Skeans MA, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2018 annual data report: kidney. Am J Transplant. 2020;20(suppl s1):20-130.

vii Meier RP, Longchamp A, Mohiuddin M, et al. Recent progress and remaining hurdles toward clinical xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation, Mar. 2021, doi.org/10.1111/xen.12681

viii Cooper DK, Gollackner B, Sachs DH. Will the pig solve the transplantation backlog? Annu Rev Med. 2002; 53:133–147.

ix Ekser B, Ezzelarab M, Hara H, van der Windt DJ, Wijkstrom M, Bottino R, et al. Clinical xenotransplantation: the next medical revolution? Lancet. 2012; 379:672–683

x Ekser B, Cooper DK, Tector JA, MD, et al. The need for xenotransplantation as a source of organs and cells for clinical transplantation. Int J Surg. 2015 Nov.; 23(0 0): 199–204. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.06.066

xi Orian Research https://www.orianresearch.com/report/xenotransplantation/1798312

xii Ekser B, Ezzelarab M, Hara H, et al. Clinical xenotransplantation: the next medical revolution? Lancet. 2012; 379:672–683. [PubMed: 22019026]

2. Key xenotransplantation market players

Currently, xenotransplantation research is mostly driven by academic groups around the world, principally in the US and Europe,xiii with government funding from national agencies such as the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF). In addition, biotech companies such as US-based eGenesis and United Therapeutics are committed to expanding the availability of transplantable organs. Both companies use gene editing platforms to manufacture genetically engineered pig organs and cells such as eGenesis’s HuCoTM kidney and United Therapeutics’ UKidneyTM to be transplanted into patients with end-stage organ failure.

The xenotransplantation market’s rapidly growing potential could be further increased by more intense collaboration between different players:

- Traditional large PharmaCos have significant gene editing expertise using CRISPR-Cas9 and other technologies. In addition, these global players have deep experience of engaging with regulators to shape markets in key countries and regions – a critical challenge that must be addressed to maintain the xenotransplantation market’s current growth trajectory (see Section 3).

- Companies focusing on animal health can help to improve the breeding and health of genetically engineered pigs to minimize the risk of zoonotic infections in organ recipients. Large PharmaCos such as Boehringer Ingelheim which combine human pharma and animal health capabilities are particularly well placed to overcome this scalability challenge.

- Governments need to increase funding to academic groups and biotechs to maintain innovation in xenotransplantation R&D and ensure strong, sustainable collaborations across the sector. This financial support is politically and socially imperative, given xenotransplantation’s projected impact on future healthcare and the potentially sensitive allocation of available engineered animal organs.

- Venture capital (VC) and private equity (PE) funds should also make more capital available for R&D and clinical development programs, given recent research and clinical breakthroughs and consistently increasing worldwide demand for eligible donor organs. We anticipate a high return on investment for first movers and early followers and there is already evidence that some VC and PE funds have got this message. For example, a total of 28 different investors worldwide have participated in three eGenesis funding rounds since January 2020 worth a combined total of $263 million, according to data compiled by PitchBook.

xiii Leading academic groups include the Xenotransplantation Program, Department of Surgery, The University of Alabama, US; the Thomas E. Starzl Transplantation Institute, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, US; the Transplant Division, Department of Surgery, Indiana University School of Medicine, US: the Department of Surgery, University of Maryland School

3. Key regulatory challenges in a rapidly evolving xenotransplantation market

Animal-to-human organ, cell and tissue transplants are by their nature bound to attract controversy. The sheer speed with which xenotransplantation could enter mainstream clinical healthcare in the next few years means that regulators and supporting companies need to start thinking now about the key legal, ethical, and operational challenges on the road ahead. The risk of ignoring these challenges is that the market’s growth will stall and patients worldwide will fail to benefit from xenotransplantation’s full potential to improve health outcomes and save lives.

We believe the following challenges require the most urgent attention:xiv

xiv Kwisda K, Cantz T, Hoppe N. Regulatory and intellectual property conundrums surrounding xenotransplantation. Nature Biotechnology | VOL 39 | July 2021 | 796–798 | www.nature.com/naturebiotechnology

4. Why xenotransplantation promises to deliver an increasing return on investment

Everything in xenotransplantation from an investor’s perspective hinges on the science – and to be clear, you don’t need a science degree to appreciate the dizzying pace with which recent advances in clinical technologies are transforming the potential for using animal material in surgery on humans.

Take just one illustration – xenotransplants using pig organs in human heart and kidney operations. In the early 2000s, prolonged survival of xenotransplants from pigs to non-human primates (NHPs) was recorded, especially in heart and kidney operations. The removal of one gene from pig organs reduced rejection and extended the survival of a pig’s heart in NHPs by up to six months. However, significant challenges remained.xv,xvi

xv Kuwaki K, Tseng YL, Dor FJ, et al. Heart transplantation in baboons using alpha1,3-galactosyltransferase gene-knockout pigs as donorsinitial experience. Nat Med. 2005;11(1):29-31.

xvi Ekser B, Li P, Cooper DK. Xenotransplantation: Past, present, and Future. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2017 December ; 22(6): 513–521. doi:10.1097/MOT.0000000000000463

Where we are today

Recent advances in gene editing such as the CRISPR-Cas9 technology have facilitated the production of genetically modified pigs and allowed researchers to accelerate development. Modifications of the pig’s genome aim to prevent “xenografts” from non-human sources being rejected by our bodies via different mechanisms and minimize blood clotting problems after xenotransplantation surgery.xvii

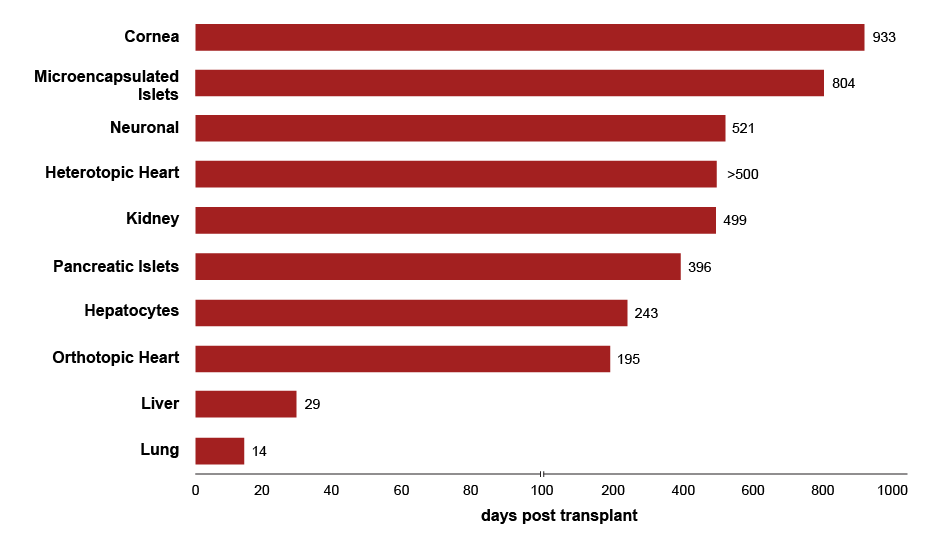

Meanwhile, the survival times of xenotransplants in pre-clinical trials from genetically modified pigs have increased to as long as two-and-a-half years (933 days) for a cornea operation and around 500 days for heart and kidney transplants (see Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3: Longest reported survival times of pig organ and cell xenotransplantation in preclinical trials

Source: Based on Kuwaki K, et al. (Nature Medicine), 2005 , Ekser B, et al. (Current Opinion in Organ Transplantation), 2017. (See references xviii and xix.)

These advances mean the first clinical trials involving humans may be on the horizon.

What is required to make xenotransplantation scalable

Despite this increasing accumulation of positive data, key challenges need to be addressed by researchers and clinicians before national, regional, and global regulatory authorities can support large-scale animal-to-human production and wider use of xenotransplantation in surgery.

These challenges include:

- Identifying the most effective gene modifications for further minimizing or eliminating xenograft rejection

- Minimizing the risk of complications, especially zoonotic infections

- Identifying the best supportive medical regimens to safeguard the patient

We believe these and other challenges will be overcome in the foreseeable future, as progress in xenotransplantation R&D and clinical practice continues to gain momentum with the first clinical trials expected either in 2023 or early 2024. PLS companies and investors can of course choose to wait until the market is more mature. However, they risk losing out to bolder rivals who gain a first-mover advantage by spotting rapidly emerging fast-growth opportunities in xenotransplantation.

Our advice: Don’t sit on the sidelines. There are big rewards in xenotransplantation for investors who keep up to speed with this increasingly promising market.

xvii Meier RP, Longchamp A, Mohiuddin M, et al. Recent progress and remaining hurdles toward clinical xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation, Mar. 2021, doi.org/10.1111/xen.12681

Dr. Malte Kremer, former Partner, and Edward Hamer, former Director at Strategy& Germany, as well as Sebastian Kwisda, former Manager at Strategy& Switzerland, also contributed to this article.