Capturing the promise of shared services

Executive summary

For most of this decade, shared services has been trumpeted as a new means to deliver support services more effectively and at significantly lower cost than traditional delivery models could. Although most of the leading companies throughout the world have adopted the model in one form or another, many have been disappointed with the results. Others, however, have achieved benefits well beyond their expectations. One reason for the varying levels of success is that models and practices have evolved so quickly over the last 10 years that the term shared servicescan mean vastly different things to different organizations. At one end of the spectrum, shared-services organizations are nothing more than old-fashioned head-office central services with a new name. At the other end, where the most successful companies fall, are stand-alone service delivery organizations that are operated like any other business unit.

In working with and talking to hundreds of organizations that have implemented shared services in the past decade (most of them in the past five years), we have observed three predominant shared services models — all of which are still in use today (Exhibit 1).

1. Organizational Consolidation. Many early shared-services implementations (and even some recent ones) were intended to capture scale efficiencies within their organization. An executive was appointed to implement the new shared-services model and after the structure was established, the shared-services head began negotiating with business units about the services that would be “consolidated” and sold back. The focus was on consolidation rather than fundamentally changing the way services were delivered. And because this solution focused primarily on centralizing service delivery, business unit managers fought against it. In the absence of true restructuring, it was often not possible to reduce costs. This resulted in a shared-services organization with few of the benefits but many more of the headaches of implementation.

2. Supply-Side Restructuring. Many organizations understand that in order to fulfill the promise of shared services, fundamental restructuring of support services, not just consolidation, is required. The best implementations involved a major functional reengineering effort to eliminate work and simplify processes; this was led at a senior level to make the supply side as efficient as possible. In general, the results were positive: Overall costs were typically reduced by an initial 15 to 20 percent, and performance was maintained through the transition.

However, not all organizations have succeeded with this model. Some shared-services managers have been too aggressive in out sourcing activities such as finance and IT without fully understanding how to manage external relationships. And business managers have at times not been fully engaged in the process, seeing it as a functional initiative to take away control. Without both sides working together to further drive down costs, the potential of this approach is limited.

3. Business-Driven Solution. The new wave of successful implementations has recognized that around 40 percent of the total benefits available in a shared-services implementation comes from demand management, shared-services managers working with the businesses to achieve a cultural change in the way they think about support services (Exhibit 2). The goal is for business managers to think of support costs as controllable rather than as a head-office allocation. Clearly, all of the supply-side restructuring and reengineering is still necessary, but successfully managing demand requires that business unit managers rethink their support requirements and be actively involved in the design and delivery of services.

The focus of shared-services managers has shifted, from providing functional excellence to users, to providing functional adequacy in which the businesses determine their needs and the level of service they can afford. To achieve this cultural shift, many organizations have adopted governance mechanisms and processes that involve key business and functional representatives in the ongoing decision-making process. Generally, a shared-services board and a shared-services buyers committee are the primary decision-making bodies (Exhibit 3).

These groups meet a few times during the year to define required services, monitor performance, and approve budgets. It’s critical that the process not become a legally oriented, contentious environment — a culture that will soon sink any shared-services initiative. Rather, what successful organizations are doing today is creating a cooperative model. Buyers committee meetings are short, focused on three to five key business drivers, and depend on one- to three-page service-level agreements. These meetings provide a mechanism to ensure business units maintain control without having to own the activities. Thus, much of the resistance to change from the implementation of shared services is eliminated (Exhibit 4).

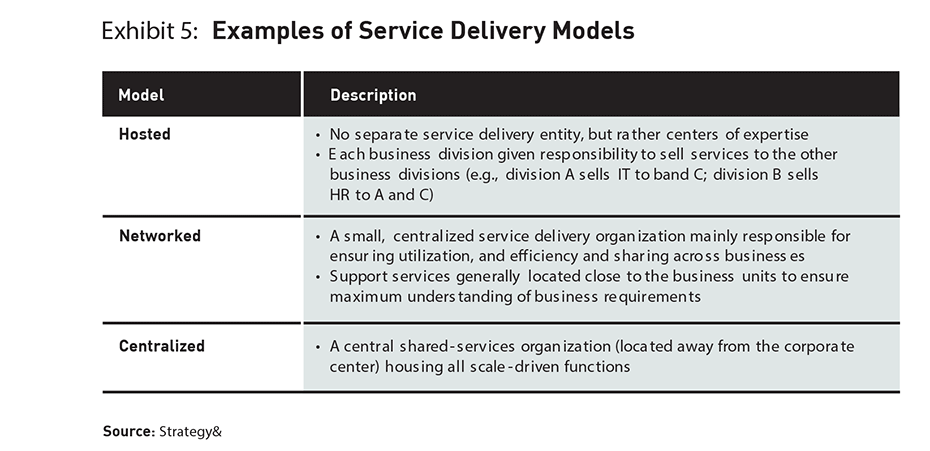

This approach has demonstrated that the overall structure is less important than getting all the major stakeholders involved in developing the solution. As a result, more-innovative service delivery models are beginning to emerge that locate services with the businesses to maximize customer intimacy, while being managed centrally to achieve scale and utilization advantages, and leverage expertise across the organization (Exhibit 5). With a successful implementation of both demand-side and supply-side initiatives, companies that have implemented a business-driven solution have been able to successfully sustain cost savings of more than 30 percent.